Lately, I’ve been pondering ponds. I even entered one trying to clean it up. The funny thing about ponds is they are full of things we can’t see without a microscope. A real clean up requires undertanding the role each little microbe plays in making the pond flourish by feeding larger organisms, or by supplying oxygen and other vital, or possibly toxic compounds. We step into the muck if we dare. Our good intentions take us to the plastic bottles and styrofoam cups people carelessly toss into the water. Those are obvious. We know they don’t belong. But to optimize the pond’s awesomeness, we’ll need some deeper understanding of it. We might have to submerge ourselves entirely, top hats and all. All this is an anology. Moral and ethical theories, political theories, religious theories, economic theories, and theories of social transformation – all exist together in the pond of life. And they work the same way. Some things obviously don’t belong. Other things require more thought. In a clean up effort, it’s easy to get help with the plastic items on the surface. Everybody can see that. It’s harder to get help with the-complexity-of-who-knows-what-is-lurking-at the bottom of the pond. But it’s actually that subtle, harder-to-understand stuff that matters most. What if it kills all the fish and plants? What if it kills us? Today we’re going to explore it. Ready?

I’ll start with a quick review. We started coming down from a very high mountain of metaphysics, where we had asked what the most awesome thing possible could be. We had learned to put on a multiversal mindset in asking questions like what we were, seeing that Maximized Awesomeness was true. In other words God is real. From there we descended into our own world, the world of axiology. We asked how to maximize awesomeness in this world and I told you we would try to build from the ground up, but seeing that many others had already done the same thing, I thought it would be a good idea to take an inventory of what had already been said. What was already in the ecosystem? What was already in the pond? How did it all work together?

The first thing I pointed to in the pond that looked like it might be worthy of optimizing was Aristotelian virtue ethics. Aristotle introduced us to the idea that the best way to live is to acquire the ability to judge where the optimal balance is between too much or too little of a good thing. We looked at the example of honesty. While deficient honesty may be an obvious flaw of character, it’s easy to take the position that there can be no such thing as being too honest. But really? No, you can even have too much honesty. What if someone confesses to you all of their personal flaws? Is that a good thing? Maybe you think so. But what if you had ten employees and the other nine had worse flaws than an exceptionally honest penitent employee, but they were all kept quiet about them? How would that affect your decisions?

With Aristotle, you’ve got to know when to hold ’em and when to fold ’em. Aristotle gets criticized for not being specific enough about that. He doesn’t really have a system. People like systems. Aristotle did have systems but not when it came to virtue. All Aristotle has here is a general description.

For an actual system of morality, we might turn to Immanuel Kant. Kant satisfied the common demand for a moral system with a sort of one-size-fits-all theory. With Kant, you can make up ethics as you go since every situation is different, but just stick to a few basic rules. Number one, ask yourself what the world would be like if everybody did what you are considering doing. Number two, don’t use people. These two things are your duty. Anything else you do is not duty. It’s just stuff that makes you happy – even when you do good things. Kant reduced morality to duty because duty is something logic tells us we should all understand and embrace. It’s what he called a categorical imperative. Society breaks down without it.

We’ll add this simplified version of Kant’s categorical imperative to our tool set but it won’t be the only tool in the shed. A lot of people embraced Kant’s system. Look closely though. Kantian ethics aren’t the same as utilitarianism and consequentialism, which were also very popular. Utilitarianism looks for maximized awesomeness in the net end-effect of decisions. Consequentialism is more self-interested. In consequentialism, or any form of utilitarianism, it’s good if the net result is good for the most people and their cumulative happiness. In Consequentialism, it’s good if you personally gain by the action, or maybe the company you work for or the team you are with. Even though Kant asked what the world would be like if everybody did what you did, he was neither a utilitarian nor a consequentialist. For Kant the ends don’t justify the means. The means have to be rejected if anybody gets used or abused.

It would be better if there were no losers in the outcome. Wouldn’t it? Of course it would.

All of this applies to personal decision making. Kant, and the utilitarians as well, might have applied their theories to corporate or national decision-making too, so let’s take a look at some of the bigger critters in the pond. If our corporations and our nations lived virtuously, wouldn’t that be sweet? Do you find that nations and corporations live according to self-interest? Do you find they use and abuse one another as a means to their ends? What principals do they apply? How might this apply to where you work?

It’s something to think about. Now not everybody agrees with Kant. There are other ways of looking at things. Before Plato, Socrates and Aristotle, there was Homer. In Homer’s world people who were considered heroes for deceiving and hurting others for personal gain – people like Achilles and Odysseus. It’s a timeless thought, even in the Christian era. After the Middle Ages, Machiavelli wrote a book for rulers recommending winning by any means, using virtue only ostensibly as a way to get ahead, gaining as much power as possible. There have also always been physicalists and materialists – people who don’t believe there is anything more to this life than the physical stuff you can see and touch. There’s no shortage of people who’ve thought about this. Many people have asked the same question if every age – if the physical world is all there is, then what’s the point of morality? Machiavelli asked this question, even though he was the son of a pope – (a pope who broke the rules at least once, obviously).

Not all who disagreed with Kant were materialists though. Freidrich Hegel, for instance, like Kant, was a very religious person. Hegel introduced another helpful tool for measuring the pond. He was an early ninteenth century German philosopher who was interested in the gist of things, or in German, “geist’, or in other words, the “spirit” of the times. “Geist” is German for “ghost” – as in Holy Ghost. Hegel asks the question, what is the spirit of God and of the devil doing in humanity? What is the common mind saying? Where is it leading? What is the gist of what is going on in the spiritual realm? Hegel was looking at the whole pond, asking not about what its chemical composition was so much as what the pond did and what it was going to do in the future and ultimately become, given its spirit.

To compare them, Kant is like the Moses of the pond, giving a post-Christian world the Law without a church or Bible. Hegel is like the Elijah of the pond, giving the post-Christian world prophecy without a church or Bible. Hegel was concerned with the direction of humanity as a whole. This started a trend in the philosophical world that hasn’t ended. We all want to coach the whole world from the sidelines. We all want to control the outcome of the human experiment. Don’t we? I know I do. And we want to know where it all goes.

Hegel looked at humanity as a maturing single organism whose mind or spirit was in a learning process. The life of all humanity, like the life of an individual, was a journey. If there was a general consensus about how to look at the world that might represent the spirit of the times in any given age, there were also critics that would come along, noticing its flaws. Their voices would then get louder and louder until change became inevitable. Then when that change became “the new normal” their new synthesized way of thinking would itself become the subject of criticism. There was a pattern in the history of philosophy – a cycle of thesis, antithesis and synthesis. Hegel looked at all of history this way, seeing in it a sort of volley of settled ideas that would get disrupted and replaced, only to have the new way of thinking subsequently become disrupted and replaced itself. Like a conversation, where two people are talking and learning from one another, ideally growing in their ideas, Hegel called this dialectic, as in a dialect. Better yet, Hegel didn’t just look backwards at this historic dialog. He looked into the future to see where this ebb and flow of epoch-spirits would ultimately take the world. Where was the conversation headed? And he thought he had an answer – his own thoughts would be the culmination of its thinking. His human introspection, his self-reflection of humanity as a whole, became the new spirit of our own times. In hindsight, Hegel was incredibly arrogant. Historians have a way of judging the past and exempting themselves from its faults, as if they had learned all of its lessons.

Hegel’s dialectics led to Karl Marx. Unlike Hegel, Marx was a physicalist, who replace dialectical idealism with dialectical materialism. He was an atheist whose thought about the human condition and mind would ultimately center around man’s most common activity – work. He saw a shift not just in philosophical thinking but a tension between owner and worker classes in the industrial age. He took up where Adam Smith left off on the division of labor for the sake of efficiency, and like Hegel, he looked ahead. He noticed that workers were always alienated from their work because the efficient division of labor would always mean doing more work for less money as competition increased. I think you know about the Communist revolutions that took place in Russia, China, Eastern Europe and South America that were inspired by Marx’s theory, so I won’t repeat all that. But if you think about it, the revolutionary spirit was alive and well long before Marx. It took over right around when America was born in the enlightenment age, thanks to writers like Rousseau and Locke, and also thanks to something very mechanistic about the industrial age. The industrial age was an age of reason. Like factories, our reason was very mechanical. Kantian ethics were a matter of pure reason – very mechanical.

Looking at the big picture in Hegelian terms, expansionist Communism was just an extension of the revolutionary spirit of the industrialist, rationalist age. At that time, thanks to Darwin and Galileo, traditional Christian morals and authority were subject to question, as Hegel showed. Genesis was replaced by the big bang. Historians, philosophers, educators, scientists, all took part in rejecting religious tradition in favor of ideals of reason and science. America was founded on religious freedom as an ideal. Europeans thought Americans were idealists. I don’t know if I agree. Idealism is sort of naive. The constitution seems to be pessimistic, even cynical to me. It’s designed to protect the people against a predictably abusive government, as if no government would ever be capable of living according to ideals. But I’ll leave that topic for another day. My goal here is just to summarize what we find in the pond and to see if it needs to be tweaked at all for the optimization of awesomeness. Religion lingers on in the pond as a remnant but it is no longer the dominant force in what we might call the human mind. All of this variety of philosphical thinking, both physicalist and dualist whirls around in the pond together with religious tradition to this day.

The Danish philosopher, Soren Kirkegaard, like Kant, was deeply religious but he was highly critical of Christianity, Judaism, Islam and deism. He thought of himself as a missionary to Christian missionaries. He rejected both the rationist spirit of Hegel, with his prophecy for the future of human thought, and the Kantian system of pure reason. If Kant appealed to pure reason, Kirkegaard appealed to pure faith. In the Bible Abraham is commanded by God to sacrifice his only son, Isaac. This command makes absolutely no rational sense. Kant , in a footnote, even admits he would say this passage couldn’t have been God making this command because God is perfect and therefore would never ask anyone to violate a moral principle. For Kant, if everybody sacrificed their children, everyone would be dead. That would be horrible. Therefore, God could not have commanded Abraham to do this. Kirkegaard abandons reason. He loves the Abraham story precisely because it is so absurd. For Kirkegaard, there is nothing more exemplary for the man of faith than Abraham blindly doing as God asks.

He wrote two pivotal books – one titled Either, the other titled Or. Either a person is a person of the world, a person of the senses, which Kirkegaard called an aesthetic life, or they are ethical, living a life of faith, in the will of God. The aesthetic life is natural, physical, mechanical, earthly, sensory, pleasing the senses, carnal. Reason and the intellectual enterprise of philosophy, pleasing the mind, are all part of the non-faith category, which is all about personal pleasure. All of the lofty reasoning of Kant is just intellectual foreplay for the flesh in this. Kirkegaard thinks Kant’s system is fleshly. It’s all a distraction from the faith-based ethical life. There is really only one choice to make in life – either choose faith, or choose the worldly system with all its endless, and often sophisticated distraction. Ethical systems based on reason are nothing more than a distracftion for Kirkegaard, from the blind obedience that is the only other moral choice. Choose one or the other. There is nothing in between.

Faith is a sort of trump card on philosophy this way. It is based on itself rather than on reason, just as reason is based on itself rather than on faith. Which sort of person are you? A person of faith or of reason? For Kirkegaard, it is impossible to be both.

Then there is another side of Kirkegaard. His division of reason from faith opens up a new realm of philosophical thought. What happens when you strip Christianity of its intellect? Christian intellect brought us something called teleology. Teleology is functionalism. It says that the function of sex is reproduction. Therefore, it is wrong to have sex that cannot produce children. Taken to an extreme, even inside a marriage, one should not enjoy sex because enjoyment is not its function. This precisely the sort of rationalism within Christianity Kirkegaard rejected. All he cared about was faith. Divine inspiration could be reasonable, but it didn’t have to be. Reason flowed from the divine will. The divine will was not subject to reason. It just is. So also morality – it just is. It exists in and of itself as part of the divine will by the creative work of the Holy Spirit.

For those of faith, Kirkegaard may have had something there, but for those who had already rejected religious tradition, whether full-on atheists or leaning toward the pantheism of Spinoza, Kirkegaard’s antirationalism left a void that in the absence of a divine command, had to be discovered somewhere else. If out with functionalism, in with existence. We knew that we were, without definitions. As such, we were free to invent ourselves.

I’m not sure how healthy all this is. Among Christians, I see a large number engaging in a sort of “name it and claim it” work of the Spirit as they move along with God irrationally, defining morality and the divine will as they go. Among physicalists, I see a similar problem. There, there isn’t even a Bible to give them guidance. Morality itself may as well get tossed out as useless. How convenient that Kant and Hegel were destroyed by Kirkegaard. Each person could now decide what was right or wrong in their own eyes. Neitzsche was content with this. God was dead. So was morality. There was no basis for anything. Finally, we could be fully human. We could even be Machiavellian, and without any heavy guilt trips.

This leaves the pond an utterly dangerous place to be. No one can trust anyone else in it. Each creature there is in it to serve their own appetite. You are nothing more than a stepping stone to their gain. The advantage of being a rational animal is cunning and deception. It has nothing to do with overcoming any animal instincts we may have in favor of some higher goal. Maximizing kindness in the pond would certainly make life nicer for everyone, but if anyone suggests that is their hope, then run. It is a ruse. They are only interested in taking advantage of your gullibility. Your death is near. They lie. Run!

Fortunately, Neitzsche was wrong. We started this inquiry from the high places of metaphysics precisely because I knew that in our descent into the valley, we were going to encounter him in the scum of the pond found at its lowest point. So let’s circle back. God is not dead. Neither is virtue. Nor are worlds beyond our own. And indeed there is right and wrong, good and bad, even if there is no evil. I have proven this in my free Pamalogy 101 course, where you can earn yourself a top hat if you pass. Try it. You’ll never be the same.

Existentialism only leads to nihilism for those who choose, or are led into, unbelief. Kirkegaard gave birth to existentialism in his rejection of Christian rationalism and teleology, but he was not himself an existentialist. He was a Lutheran fundamentalist. He was morally grounded in the words of the Bible that Luther didn’t remove. Neitzsche and Kirkegaard were both philosopher poets who had incredible insight into the human psyche. No one questions their genius. They were highly lauded by the respective communities that followed them. They stand out as the best philosophy has to offer to this day, far ahead of the pack. Yet, Neitzsche would laugh at Abraham. He would be triumphant in mocking God so that man might live and take credit for his own achievements. He would want us to face death boldly, seeing only what was here, seizing its opportunities. Kirkegaard would not likely exist in Neitzsche’s world. Both would be fools to one another.

So that’s what’s in the pond. As a materialist, Marx might have loved Neitzsche, as so many academicians have. A few Communist leaders have turned atheism and Neitzschean humanism into national religions. Christians in Russia, when sent to the gulags under Breshnev, were often considered insane. Bible believers today are often lumped together by progressives as hate groups. Conservatives, in turn, view this as something called TDS – Trump Derangement Syndrome. What we find in the pond is a sort of cognitive dissonance, an irreconcilable difference of visions and beliefs. The only possible way to turn all this wisdome into a single system is to ask how we can manage its toxicity without exterminating or otherwise irradicating a significant portion of the pond.

We’ve been sketching the philosophical world with a very broad brush so that we could quickly get back to where Pamalogy fits in with all of this. Here we are at the bottom of the pond getting a fair, if too quick a look, at what we’re dealing with. We see that we can’t reconcile it without some Draconian measure, so we’re going to have to leave it be, but I do think I have a solution that may reduce its acidity. I call it a pamalonomy. And if pamalonomies work, I think I can resolve some other problems as well.

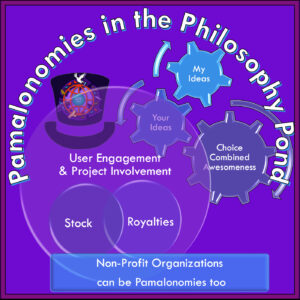

So what is a pamalonomy? It is a socially conscious business enterprise or an association of enterprises that gives buyers and sellers some form of owenership, such as voting class stock, royalties or other rights and privileges based on individual participation as agreed to by an original board of directors, or alternatively, it can be a non-profit business. Pamalonomies are strategically non-competitive. That is, they support one another for the sake of net societal impact for good.

If you read the Mission Statement for the Pamalogy Society you will see that pamalonomies are an important part of our work. We have a teaching arm. And we have a reaching arm. The teaching arm provides vision and direction. The reaching arm, turns words into action through enterprise. As such, the Pamalogy Society is an incubator for strategic high impact concept stage enterprises such as the CounterChecker. I’ll use this one example to illustrate my point.

The CounterChecker, you may recall, is a fact checking web site platform that I designed, which makes fact-checking accountable by opposing sides on any question. I’ve even described it as utilizing a Hegelian dialectical methodology. What I mean by this is that a set of facts will be presented – a sort of offical set of facts, only to be challenged by other pertinent information regarding it that results in a new set of facts once it’s hashed out by a counterchecker – some one on a different research team. Teams will typically be divided up based on ideological preference. Then that set of facts presented by an ideological opponent, is also subject to scrutiny and revision, as well, and so on – until the idea is fully vamped and revamped. Whereas, most fact-check sites serve to put an end to a discussion by favoring one side or the other, the CounterChecker begins a discussion and lets each side have all the input it needs – more like we would be doing in a trial, where there was a prosecution and a defense.

Presenting multiple sides, the CounterChecker is an anti-censorship fact-check platform. Only if you, as a research journalist, do have some counter-information to add, just be sure you can back up your story. Each contributor gets graded. Scores affect credibility. Think of it as a batting average. If you want a following as a journalist, and you want to be paid more, you need to do your homework. That’s what the CounterChecker is for. It’s like a professional sport. And since it can cover any subject, it will be like a fact-checked Wikipedia. Very useful on any topic.

As a sport it will be fun, not just useful, and it will also be lucrative because it is a pamalonomy. If users of the platform own the stock, the research journalists will be in business for themselves. They won’t just be paid for the traffic they generate, they’ll be paid dividends and can trade the stock they’ve earned. There might also be royalty rights associated with the CounterChecker. When the CounterChecker is syndicated as a plug-in for social network platforms like Twitter, Facebook and and even conservative platforms, which would otherwise be opposed to fact-checking, those platforms would have to pay the CounterChecker for use of its content. That would convert to shares in royalties for content contributors.

As I’ve said before many times, we need to raise $1.4 million to develop the CounterChecker platform. Nothing will be developed without raising money first. To prevent this money from coming from outside investors, it will come in the form of donations to the Pamalogy Society designated for the project. That’s how pamilonomies work. I’ll talk more about pamilonomies next time as I discuss how they solve some of the problems found at the bottom of the pond. For now, we’re out of time. Ciao!