Can’t we all just get along? In a household of constantly quarreling brothers, these were words I often heard my mother say. And in my house, we didn’t just argue about trivial things like what was fair or who changed the rules in a card game. We had conflicting religious and political ideas too. There were ongoing disputes. Mom was a die hard Presbyterian member of the choir. Her mother played the organ and her father was a deacon, but she was happy to sacrifice dogma for karma when it came to her Catholic husband and opinionated children. Then, in the midst of it all, as we were growing up, came some discussion of ethics from a philosophical perspective between me and my older sibs – as if that could settle certain scores. We never finished what we started on that but today, we’ll pay some tribute to Mom by continuing that hopeful conversation in the search for the true meaning of happiness. Ready?

Assuming you’ve been following this blogcast episode by episode, like I’ve repeatedly recommended, you’ll recall I’ve been mentioning theories of theories as an ecosystem of theories. Today, we’ll start to explore this.

I should state up front that the idea of an ecosystem of theories is a little different from the getting-along theory of John Rawls. Rawls was a teacher at Harvard whose political philosophy became the backbone of today’s liberal political theory. “Rawlsians”, as they are called, believe that practical politics will find a common denominator that can glue us together so long as it doesn’t expect agreement on comprehensive doctrines. As an example, this would mean that Presbyterians can agree with Catholics to disagree about the Pope, since that is part of a comphrensive Catholic doctrine that simply can’t fit into a Presbyterian’s world view, but they could still work together on points they would agree on – for instance they could support laws that protect citizens from killing each other in the exercise of individual liberty.

Rawls also very explicitly believed that we could all agree to policies and law that helped the poor and disadvantaged. For Rawls, helping the disadvantaged was of the highest priority no matter how much those policies might adversely affect the wealthy. On the flip side, helping the wealthy is perfecftly wonderful for Rawlsians, so long as it helps the overall welfare of the least advantaged. Certainly, keeping an eye on “the least of these in our midst,” as Jesus might have put it, is a point on which both Catholics and Presbyterians would agree. It’s a common denominator.

I regret that Rawls deserves more attention than I have available to give here. He was mainly concerned about the poor having a voice in government and about their access to participate as civil servants and with equal opportunity generally. He wasn’t an egalitarian. His concern with outcomes was limited to how far up we could bring the most disadvantaged. Rawlsianism matters because at the heart of Pamalogy is the maximization of awesomeness. Imagine a world in which the many are flourishing, but a few are hopelessly trapped in poverty and misery. Would that be a society experiencing the maximization of awesomeness? Certainly not if those fortunate enough to be flourishing had a conscience. It reminds me of the curious image of myriads of the redeemed worshipping in heaven somehow maximizing their own everlasting beauty in glory while yet being oblivious to the permanent torment of those in hell, many of them their own former friends and family members.

Sadly, today most are in the poverty trap, living pay check to pay check, if not on the dole, while the few are flourishing. Either way, pamalogists will likely be very sympathetic to Rawlsianism. Awesomeness is not oblivious to suffering. It is aware. But Pamalogy isn’t Rawlsianism. There are other values at stake. To start a description of them, I’ll inventory through some competing ethical, cosmological and political theories. I’ll begin with an introduction to Aristotle’s values ethics since many in my audience are non-philosophers. As always, my assumption is that you are interested in awesomeness. The Pamalogy 101 course and supplementary Season 1 Blogcast serves as an introduction to philosophy through a side door, where our focus is on the philosophy of awesomeness specifically.

So back to Aristotle. Ethical theories are types of comprehensive doctrines. We’ll find in Aristotle just that. Rawls excludes comprehensive doctrines from the conversation for the sake of designing an ideal political system of a constitutional representative government. Constitutional government may be essential for optimizing awesomeness, but when it comes to comprehensive doctrines, Pamalogy is likely to look for systems that balance and offer representation of what we truly believe, in a more parlimentary fashion that avoids some of the pitfalls of two-party/uniparty systems. As well, beliefs change, so pamalogists might be cautious, seeking to temper fluctuation in baby steps of experimentation, referred to as “pamalonomies.” We wouldn’t exclude comprehensive doctrine from the conversation in any of that.

Furthermore, and this is something of an indictment on our modern technological age, we wouldn’t want history to be buried or revised to suit the whims of successive generations as we select what we preserve, even if a majority was offended by it. Neither would we want cultural groups with whom we disagree to be suppressed. A common denominator approach might be oppressive both for making the best of today’s competing values and for applying majority sentiments to how we view the past. History’s voice should be as authentic as the many voices of the present. Balance is not a reduction to what we hold in common. It is something that involves what I’ll call “street smarts.”

This brings us to values ethics. Aristotle believed that ethical rules should be flexible. A good sense of how each situation might apply, as he saw it, would need to be acquired with experience. Spelling it all out with specifics would be futile since new situations would always arise that would make exceptions to the rules the better choice. And here you have it. The Greek word for practical wisdom – φρόνημα – might be thought of as “street smarts.” There are some things you just can’t learn in school. For Aristotle, this held for individuals and also for whole societies, which is why in the first book of his Ἠθικὰ Νικομάχεια he made it clear that politics was a higher value than personal morality.

I don’t know if I agree that it is. I think most of us would take a both/and rather than either/or approach on that. We are aware that you can’t legislate morality. You can, however, prevent people from injuring one another through law, and it is also true that the decisions of kings have relatively profound consequences compared to those of the masses. But as to the power of the individual, a pamalogist might readily believe that in the kingdom of countless heavens in the Multiverse, small actions reign over larger domains than first meet the eye. The power of what might seem to be an uninfluential person of no means in prayer or in action may easily exceed the power of a king to affect just one world for good.

To be sure, Aristotle wasn’t thinking about that. If Plato was a rationalist whose mind was always in the heavens, like mine is, Aristotle was an empiricist, whose mind was very much set on things within one observable world. And that’s not the only difference. In fact, the whole idea of virtue was different for Aristotle than it would be for most of us. In Aristotle’s day virtue was a manly thing. I won’t suggest we embrace it as it was. I’ll stick to what we can glean from it. The Greek word for virtue, ἀρετή, refers first to excellence and goodness, but it was often used to mean manliness, rank, prowess and valor. Honor and respect was a soldierly thing back in the Fourth Century B.C.E., not much associated with the feminine first or foremost. The Greek idea of virtue was about character – primarily manly character or the character of a successful state. It might have to do with reputation and dignity – equally important to women, but it was also about fame, glory and distinction, which didn’t involve females much at the time.

Aristotle’s specific sense of virtue was traditional for his day and age. It might be an elaboration of the values highlighted by his mentor, Plato, as found in his work, Πολιτεία, better known as the Republic. The Republic is styled as a dialog with Socrates. So if anyone suggests the values Aristotle raises don’t have some rational foundation for being singled out, the answer is tradition – a patriarchal tradition we won’t attempt to carry forward here. Still, we should look at what the golden mean of virtues is and ask ourselves how this idea of virtues being best discovered by a middle ground, might apply today.

Aristotle singled out eleven specific virtues – ambition, courage, temperance, liberality, magnificence, magnanimity, truthfulness, wittiness, friendliness, modesty and righteous indignation.

I won’t cover them all nor repeat his examples, which if you care to you can read for yourself following the links in our blogcast trasnscript. Let’s do a thought experiment for a moment on some values on this list that are still highly prized today that might make the idea clear – truthfulness, wittiness and friendliness. We’ll start with truthfulness. If a person is insufficiently truthful, they will lie for bad reasons, manipulating others selfishly, cheating, stealing and causing damage to reputations, or getting them in trouble legally by making up hearsay or twisting facts. But if they are too truthful, they will give away secrets, spread gossip, and hurt feelings, neglecting kindness and sympathy. Or they might just be annoying, by always providing more detail about things than you have time to listen to. Some are grammar nazis, ever changing the subject in conversations to tend to accuracy that doesn’t really matter as much as what someone intends to say. It takes a lot of life lessons to master the art of aquiring the virtue of truthfulness. Truth does matter, but never in excess. And if at any point I suggest Aristotle’s ethics are situational, what I mean is they are flexible. It might not even take someone schooled in the art to recognize a true virtue virtuoso. The flexibility I’m talking about is like a good jazz musician, who practiced in chord progressions and modal licks, has familiarity with what goes with what and makes it up as he goes masterfully. There are objective criterea for recognizing it. That’s why I’m not repeating his examples. It’s about intuition and practice and may involve giftedness.

Let’s take another example. What about wittiness? That certainly involves giftedness, and again, the virtue lies in the middle. If a person has no sense of humor, they will react inappropriately when people around them make jokes. They’ll be easily offended, not interpreting what is being said as it was intended. This will cause quarrels and disagreements. Plus, if they never laugh, they’ll be unhappy and if they never make jokes, their unhappy demeanor will likely bring people down. The one who enters a room with levity, by contrast, can lighten everyone’s mood in an instant. They are charming. This can be a wonderful virtue and it can be acquired with experience. But again – extremes are to be avoided. If they never stop joking around, they may never take a moment to express compassion or address a serious problem. What if another person has a need? What if a person needs a hug because they have lost a loved one. Wit isn’t always the appropriate response in every case. Taken to an extreme, wittiniess is irresponsible, selfish and could get a person put in jail or slapped in the face. Constant witiness is also a sign of insecurity that can mask self-loathing, or become such a constant habit that it prevents a person from taking the time for sober introspection and self-evaluation. My brother’s godfather was Jonathan Winters. My father was his AA sponsor. He saved him from commiting suicide more than once. Winters was Robin Williams’ mentor in the art of improv comedy. Few of us knew how unhappy Robin Williams really was. What Aristotle was objectively aiming at was avoidance of deficiency in a virtue, or excess. For most of us, the problem is with deficiency.

Friendliness is another example – one very relevant to our era. Living in an age of social media, we know more than ever how careful we need to be both with who we are friends with and how much time we are willing to devote to them. We are also far more conscious today than we ever were of mutual consent when it comes to friendliness. When a solicitor calls with a friendly voice as if they are doing us a favor by calling, we may just hang up on them. That might seem rude. We could always make someone’s day by saying something nice, even to a solicitor, but if we were overly friendly, we would be on the phone all day talking to strangers who were using us for the products and services they wanted to sell us and actually, many solicitors would prefer it if we just hang up so they can move on to the next call faster. On the other hand, if we weren’t friendly enough, we would be rude not just to solicitors, but even those near us. Grumpiness is easy.

The real virtue of friendliness will find a middle place, not some mathematical compromise, but a wisely learned middle ground between the extremes of letting others use and abuse us and a variety of ways we could be too friendly. We would find a healthy place in the middle where we offer kindness and cultivate enough relationships at various distances that we would realistically have time for. Some of my friends don’t require much maintenance at all. They are always ready with kindness and love. Since I don’t have much time to invest in friendships, those are the types of friends I’m happiest to find. Most people have very few very good friends. Many of those friendships are dysfunctional. It isn’t just solicitors who use us. It can be those we’ve unwisely chosen. Our over-friendliness may take the form of an unhealthy loyalty. It may be holding onto toxic relationships. It might be street-wise for us to back out of certain friendships. Then again, true excellence might call for holding on even to toxic relationships in particular cases. Maybe an ever-nagging disabled Mom, for instance?

Grumpiness and lack of courtesy are simple objective measures of friendliness. It’s a no brainer that unkindness is rarely demanded in the grand scheme of maximized awesomeness. What takes more skill is realizing when tough love is called for. Maybe that would be a solution for your OCD Mom. But there are also subtle examples, such as unfriendliness by ommission. Have you ever ignored a lonely person at a social function? Maybe you lacked the necessary courage to be friendly. Some people, particularly in business functions, might feel tremendously relieved to have someone pay attention to them, no long term committment required. Picking up body language is part of acquiring this virtue. You don’t always know if you don’t at least introduce yourself. The virtue of friendliness breaks through your own shyness and comforts strangers. It empathizes, but it also very quickly intuits whether that other person’s engagement with you will mean more than you bargained for in your initial courageous approach. Friendliness actually means being very good at reading signals between the lines. Once again, it takes practice – what Aristotle termed, φρόνημα. φρόνημα is not the intellectual wisdom that solves cryptic mysteries and complex problems. That would be σοφία. φρόνημα is practical wisdom. It’s street smarts. The maximization of awesomeness involves street smarts and some masterful improvisation.

For that matter, Aristotle had his own version of maximized awesomeness – εὐδαιμονία. εὐδαιμονία is happiness. And it’s more than happiness. It’s a peaceful sort of abundant happiness through human flourishing. It’s found in achieving an ideal. It’s found in success. For individuals it’s born of a matured character that’s acquired with practice, usually by following after good examples. Societies can also mature and grow in character the same way by valuing previous successes and failures until they flourish. And just as with individual virtues there is a streetwise golden mean of values to embrace, the way societies form and act as institutions is best carried out with this same sort of middle-way wisdom.

I should mention a much more recent philosopher, Edmund Burke, here. Burke was famous for contrasting a certain successful revolution in England with the idealist revolutions in France. He was highly critical of those preaching revolution who had seen successful regime change in other countries. Overthrowing of governments was something best reserved as a last resort. New ideas, embraced especially by the young, were seldom well thought out. Sure, justice was in high demand, sometimes expressing itself with cries of tyranny and bloodshed, but what was the cost of making change? The French did not heed Burke’s prophetic warnings. Destroying all the institutions that had previously existed, they were left in poverty, without hospitals, without food, without a means of income, disease ridden and with little means to rebuild.

I won’t go into the details. My point is that Burke’s conservatism would have spared the French tremendous mysery, had they heeded his voice. Too much change, particularly violent change, is something a wise pamalogist would avoid. We can envision a better world with great clarity yet be patient about finding the best path for seeing it through. That’s what I’m working on filling out the detail for here. A United Front or a Vanguard movement, shipping guns around, is not likely to get any support from our members. We should instead progress with street-wise virtues, teaching by example, and invite Prudence to come out to play, as the Beatles, I think were suggesting. I grew up on the Beatles. “If you want a revolution, alright, we all want to change the world; but if you talk about destruction, don’t you know that you can count me out.” Prudence is a good word for it. I’m not saying it won’t involve peaceful protests at times, but it involves a middle-way. This applies both for society and for individuals.

So, at the heart of Aristotle’s ethics is character – something cultivated over time. In fact, the very word “ethics” comes from the word ἦθος, which means character, or refers to the character of a culture, as in the word “ethnic.” Good character takes time to acquire through experience and example and leads to a maturity that is the end goal of life – a flourishing happiness. Aristotle’s idea of happiness was well considered and set against a backdrop of other theories of happiness. In classical philosophy, for instance, happiness was found in the freedom from things. For Epicurious, it was freedom from suffering and torment. For Epictetus it was freedom from emotional attachments and passions. You’ve probably heard of stoicism. Stoics found happiness in simplicity. Nothing can bother a person who is free from all worldly attachments. But that is not what Aristotle meant by happiness. As he explained to his nephew, Nicomachus, neither was it pleasure that made us happy. Pleasure is hard to sustain. Nor was it wealth. Wealthy people find many ways to be miserably incomplete. And despite the Greek sense of honor, it wasn’t fame either. Particularly today we know that famous people long for privacy. So how did Aristotle define happiness?

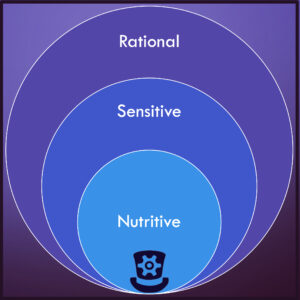

He was a functionalist who anticipated Maslow, I think, in separating three areas where we find happiness as human beings. First, there is the satisfaction we find in safety and food for survival and meeting the basic needs and instincts of our bodies. Second, there are the emotional needs we often satisify in relationships and mating. But animals have all of these. At the highest level is the rational soul seeking the fulfillment of its purpose. And its purpose is εὐδαιμονία – to be happy.

Let’s do another thought experiment. Ask someone – anyone – what they are doing. It doesn’t matter what. When they explain to you what they are doing, ask them why they are doing that. When they answer why, then ask them why that is their explanation. Keep asking why and ultimately they will eventually tell you that the reason they are doing what they are doing is that they want to be happy. Whatever we do, always seems to indirectly serve this purpose. So, for example, if you were to ask me why I produce blogcasts, I would tell you it is so I can explain Pamalogy. And if you asked me why I want to explain Pamalogy, I would tell you it is so people would have a better vision of how the world could be. And if you asked why I wanted that, I would tell you it is because it is my desire to do the most good in this world I know how to do before I die and I think Pamalogy, accurately understood, would bring about much happiness for many people for ages to come. And then if you were to ask me why I did that, I would say it was because doing that would make me feel successful, like I had achieved my goal, and that would make me happy. I would endure an awful lot of hardship and sacrifice and even suffer a great deal as I struggled to make that happen.

Similarly, with Aristotle, happiness is found in success. It isn’t necessarily a business or political success, so much as it is the fulfillment of one’s mission or sense of purpose. My own example should be useful in conveying this. Have you traced yours? Have you sent me a link to your do-it-before-you-die list, like I asked you to? I really want to see it.

I’ll wrap up my discussion of Aristotle for now by pointing to something called teleology and what became teleological ethics, thanks to the great love of Aristotle shared in the West, especially by the Catholic Church through its greatest “doctors,” especially Thomas Aquinas. The idea comes from the Greek word τέλος, which means “purpose”, “will” or “completion” – even “perfection.” For Aquinas τέλος would have meant divine will or intention. The idea of whether something is good or bad, in teleology, centers on whether something is good at fulfilling its purpose. The purpose of shoes, is to protect feet. If they have holes, or create blisters in your heels, they are imperfect shoes. They lack teleological virtue.

It’s a valid theory. The purpose of a knife is to cut. If the knife is dull and can’t cut, it can’t achieve its purpose. That makes it a bad knife until it is sharpened. If a boat can’t float, it isn’t a good boat because it can’t achieve its purpose, which is to carry people where they want to go over the water. Aristotle, and Aquinas, both applied this teleological principle to humans. Like animals, we ate and reproduced and so on, but what set us apart was our ability to think rationally. We were rational animals and the function that set us apart was our ability to reason and seek the fulfillment of our purpose intentionally, rather than as animals do, reflexively without thinking about why. This distinction in human teleology brought about a rejection of human animality so that we could be all that we could be. Augustine and other prominent church theologians, and then Aquinas inferred from this that we were sinning if we enjoyed sex for any other purpose than reproduction. Aristotle himself, not so much. Greek orgies were still quite in vogue in Aristotle’s day. Sex, including same sex relations and even pederasty were normative. What you might get from Aristotle, is that while some things may always be vices in every case, as a general rule, avoidance of excess is where virtue will be found, but even more importantly, it is the end-game that is what matters most. Success is a double game of mastering character and mastering one’s personal mission and the mission of the city-state.

That’s about all I can cram in about Aristotle here and I hope I haven’t done him too much injustice. I’m going to agree that many things do have purpose. I’m going to strongly agree that people can have a strong sense of personal mission too – a well defined course that would yield a sense of success that would make them happy both in the journey towards achievement and in finally seeing it through, but I’m not going to impose my personal experience on anyone else. I’m also inclined to think that there are many things in life that have multiple uses and purposes. Function and purpose might in fact, be very limiting concepts for determining what is right and wrong. So who is right?

In the final analysis, in seeking a balanced system of ethics we may be looking at something like an ecosystem of differing ethical systems rather than a unified theory and it will take some more episodes before I can fully describe that. In looking at such things as the purpose of sex, it will be easy to see that some forms of incompatibility may preclude us from combining every ethical system into one. Just as friends can be toxic to each other, so can ethical theories. Yet, we may also find some prudence in the balance if we look long enough. Figuring that out is something that a longstanding test of time is much better at assessing than a blogcast or two. To the likely chagrin of many in my audience, I’m not going to try to settle everything here. I just couldn’t. Instead, I’m going to continue an inventory of ethical systems because there are still more incompatibilities to uncover. And in honor of my mother, I’d really like to see to what extent it is possible for us all to get along, without dismissing whole sets of values long embraced (and still embraced by many), in favor of a possibly very destructive revolution.

In our next episode, we’re going to look at the ethical system developed by Emanuel Kant, which dear to my heart, is based on pure reason. We’ll contrast Kant’s theory, commonly known as deontology, which is about duty, with a number of consequentialist theories of ethics. Ciao!

URL for sharing this transcript page: https://pamalogy.com/2022/08/19/getting-along-how-happy-is-mom/

URL for sharing this podcast: https://player.captivate.fm/episode/d13c513b-8ddb-4b7f-aed8-428993cc752f

URL for sharing just the audio file: https://podcasts.captivate.fm/media/8015b0ba-c0d1-4c9e-8be0-182329a61644/Episode20-Getting-20Along-converted.mp3

Previous: Bad Sex