What’s the best illusion you ever saw? Have you ever been completely convinced of something and then realized you were wrong? What were the odds? Let’s think about that. Ready?

I won’t go into probability formulas or calculations. I promise. Anything involving mathematical equations goes under the hood of the machine for the engineers to deal with. There are factors that go into probability though, and that is what we’ll be talking about today, starting with a few thoughts that might just blow your mind. What we’ll be exploring is the nature of probability and how it affects truth telling machines.

I’ll start with the idea of illusions. If you go to a magic show, you’ll be sure to see some illusions. You’ll expect to be deceived over and over again and wonder how it happened. But in every day life, your expectation will be very different. You’ll assume that what you see is probably not a trick. Context matters.

Remember that word – context. Sort of obvious, right?

A Pamalogist is very much interested in context, but will tell you there may be more illusion than you realize. As a result, a Pamalogist will want you to both question and trust at the same time, depending on what type of truth you’re trying to uncover. The context of your question matters.

If you want to know for sure whether you aren’t living in the Matrix, a Pamalogist will actually step up to help you calculate the odds and tie it into the probable explanation that a grand illusion might serve a good purpose for the Maximization of Awesomeness.

And because of context, at the same time, they might also tell you to ignore what they just said, because you weren’t asking about the meaning of, or explanation for life. You were asking whether the stop light ahead of you was red or yellow as you drove underneath it. You were wondering whether you were going to make it to work on time. And while you were listening to NPR on the way to work, you were wondering whether Donald Trump actually knew there would be a raid on the Capitol on January 6th.

Whether a Pamalogist tells you something is true, may depend on what type of question you are asking. In my last blogcast I gave a sort of rushed overview of some common words used in the branch of philosophy called epistemology. Contextualism is associated with names like Keith DeRose, Michael Williams and David Lewis. You can look it all up but I’l tell you everything you need to know about contextualism as it pertains to the truth machine right here.

The basic idea, is that if you say to me, “you live in New York,” the statement you made was probably not a philosophical one. Therefore, I would tell you, “no, that’s not true.” The statement would be false. But if you prefaced the statement contextually as, “on a philosophical level, you live in New York,” I would tell you, “yes, that may be true in certain senses.” I would then explore the various senses in which that could be true. On a poetic level, I might tell you I live there in my memory, since I grew up there and have some great memories of when I was young. I would stretch the meaning of the words, “live there.” On a more literal level, I might mean that time is subject to consciousness, so that all places I have been or ever will be are where I am. And I have been to New York. I would stretch the meaning of the word “I” or the word “true.”

And that is just the beginning of such a discussion. Suddenly, context opens up a world of truthful statements and speculative statements that change the meaning of certainty and what we would refer to as true or false.

Philosophers are known to endlessly question things and hopelessly complicate them this way. I’m going to try to avoid that sort of complication here. We don’t just question everything because it’s fun to do. Questioning things can actually get seriously boring. Pamalogists will question what we see because we want everything to make sense. To be entirely accurate, a truth machine should disambiguate by clarifying context and meaning.

These aren’t just bothersome speculations. A Pamalogist wants to ask, why are we alive? We don’t just say, “what if life is a grand illusion?” or “what if I actually experience all moments of my life all the time?” We actually think this may be true. And we can show you why.

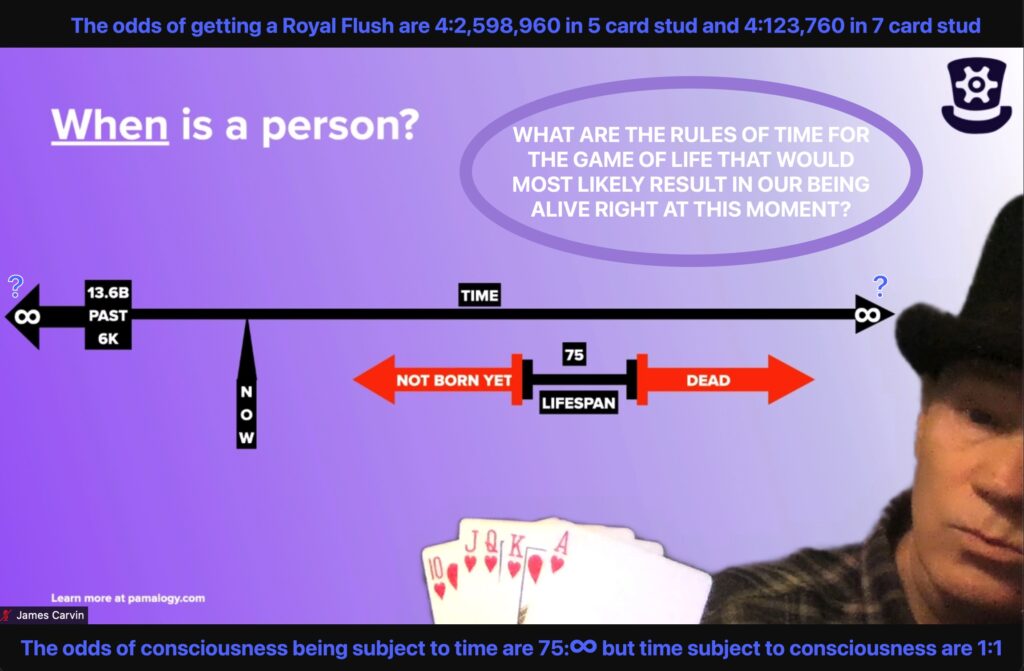

Would you like to know? Open your mind and ask yourself a few questions. The reason is a matter of probabilities. If you, being a human being, have only one life to live, however short, and the future is infinite, if not the past as well, then what’s the probability that any moment in time would be one of the few moments, relative to all time, that you would be alive? Are you aware that if time is infinite, by being alive right now you’ve defeated infinite odds?

It makes you wonder whether time really is infinite, after all.

Now, I have a brother whose very smart, and he insists that I don’t understand how probability works. In his opinion, the fact that we are alive right now, means the odds of the point in time we call “now” being one of the points in time that we should be alive, are 100%. He says that the point of probability theory is to predict future events, not past events.

I think he thinks this because he’s a great poker player, and thats how things work in the game of poker. Once you’ve got your cards, you know that the odds of you having those particular cards are 100%. Prior to that, it’s something like 1 in 52 for each card. I promised no math, so I’ll leave it at that. My brother’s point is that probabilities are for predicting things.

Let’s think about that. In poker, if you don’t throw in any wild cards, the best hand you can get is a royal flush. There are four ways to get a royal flush – the 10, Jack, Queen, King and Ace of hearts, 10, Jack Queen King and Ace of Clubs, the 10, Jack, Queen, King and Ace of Diamonds, and the 10, Jack, Queen, King and Ace of Spades. The reason this is the best hand is there are only four combinations of ways to do it. If you had four Aces, there would be thirteen ways to do that since one of your cards can be any of the other thirteen cards.

There are forty eight ways to get four aces. Four aces, plus any of the other forty eight cards in the deck.

If there are forty eight ways something can happen, given the same number of draws, the probability of that thing happening is greater than if there are only four ways for something to happen. As a result, you’re more likely to get four Aces than a Royal Flush in five card stud.

Now lets look at another poker game called seven card stud. Because you can draw seven cards instead of five, you are more likely to get a royal flush if you play seven card stud than if you play five card stud. Your chances increase by a factor of about a hundred.

So if you were to ask me what game you were playing when you got a royal flush – seven card stud, or five card stud, and I didn’t know which game it was, I would guess that you were playing seven card stud, because the chances of you getting a royal flush are vastly improved if you have seven cards to draw instead of five – about a hundred times better.

My answer to you would be something called “probabilistic abduction.” OK. Let’s disambiguate. When I say “abduction,” I’m not referring to kidnapping children. I mean it the way a philosopher means it. Philosophers use words like deduction, induction and abduction. We abduce things when we base our conclusions on the most likely explanation. If we calculate the odds to figure out what the best explanation for something is, then that’s “probabilistic abduction.”

So, now let me offer an analogy to the card game.

In the game of life, we don’t know how we got here. We don’t know what we’re doing here. We don’t know if life is a grand illusion, a matrix, or a dream of some eternal being, or what. All we know is that our being alive is like that royal flush. How sweet that of all the times to be alive, now is it. Life is short. Soon we’ll be dust in the wind. So when I question the odds of being alive, I’m not questioning whether I’ve got a royal flush, or that I’m alive. I’m questioning what game it is that presents the evident reality I have through my living senses as a perceiver in what seems like and what is called “time.” What game is this that produced this result? Is it five card stud or is it seven card stud? Is it coming from a single Universe, or many? Is it coming from a mechanical Universe acting according to Newtonian physics. Is it data in a computer game of superior beings? Or is all matter and energy and every field, just information?

What games might make the presence of my awareness right now the most likely?

I can begin with the most common guesses. If I assume that my senses are reliable for perceiving and understanding reality as they are typically understood, I can say the game of life more likely involves a short past, rather than a long one, and a limited future, rather than an infinite one. That way, the odds would have been better for me to have been alive at this point in time. With that understanding of the game, if the ultimate length of time, adding up past and future, is something like eighty trillion years, and I live eighty years, the odds of my occurrence in any of the many points in time is about one in a trillion.

Those one in a trillion odds would be better than if I assumed the game of life involved an infinite future. If the results of a hand show the defeat of one in a trillion odds, that’s very sweet. Defeating one in infinite odds, that would literally be next to impossible – yet here you are. Right about now, you should be feeling very lucky to be alive. But if the game really involved a miracle worker, then maybe your now is now for a different reason.

What are some other typical guesses as to what this game might be?

First, a Biblical view of a 6,000 year old earth would make the royal flush of your unlikely consciousness at this time a more likely game than one involving an infinite past. At least that much can be said for the traditional religious view. But I’m not sure religious people disagree with the idea of an infinite past.

Oh gosh. An infinite past, that one supposes that an infinity of time has already passed. Have you put much thought into that? Do you understand what infinity means? Can you see the contradiction in supposing that an infinite amount of time has passed? If God is “from all eternity,” like the Bible says, our personal coming into existence happened only after an infinite number of years first passed. That there is a mathematical impossibility.

For that matter, even if there is an infinite future, given an infinite amount of time in the past, shouldn’t you have been in heaven or hell long long ago? Seeing how fallen this world is, odds seem better we’re in a purgatory game right now than in heaven or hell. Don’t ya think? Usually there isn’t any torture by fire and there’s still plenty of sin. Where’s God in this world? So, in terms of the probability of what game of life is being played, the odds seem to favor a Purgatory explanation better than the explanation of a “things are just getting started and you’ve never died yet” sort of game.

Fortunately, that’s not what Pamalogists think either. We are awesomeologists. I’ll explain how all that works in another blogcast. For now, I’m pointing out the difference between results and causes. The result is that here you are alive – like a royal flush. Good for you. My brother is right. The odds are 100% that this is the case. And that’s some incredibly good news. But what game was involved that enabled it? What set of rules and parameters? What was or is the framework for the cause of the result? We may not be predicting a result, but we are asking for an explanation based on the probabilities involved in the explanations themselves. We are engaging in “probabilistic abduction.”

Probabilistic abduction works like this.

If I go to a casino, and I win at blackjack over and over again, it won’t be long before a bouncer comes out to kick me out and warn me not to come back. Nobody understands probabilities better than a casino operator. If my brother was right, then the casino operator would have no fair basis for this action. He would agree that the odds of my winning black jack consistently were evident from what happened. They were 100%. He would have no right to conclude I had been counting cards or had x-ray vision contact lenses.

I wouldn’t be kicked out because my luck was too good. It would be because the bouncer assumed, based on probabilistic abduction, that I was cheating somehow. I had somehow changed the rules of the game that produced the results we all agreed on were true. To the bouncer, I probably did it by introducing some unknown factor into what was involved in making it happen. And there’s that word “probably” again.

This is how your life is. It appears from our basic scientific instruments and sensory awareness to have been a product of evolution in a Universe that started with a big bang some 13 billion years ago. Or if you ask a Muslim, Christian or Jew who takes the book of Genesis literally, maybe you’re convinced it happened much more recently. It appears to you that the future is everlasting too. I’m not sure how the future appears to the scientific community. There seems to be some disagreement on that.

What I can tell you about it all, is that a Pamalogist thinks like a bouncer and wonders what sort of factors most probably went into the game, that favored your lucky appearance. You and I, or we, we’re not saying t0 ourselves, “hey, this couldn’t be real.” We’re saying, “how did this happen?” The idea that it is all just a dream of God who dreams – everything – always – is just one theory among many in search of the greatest probable explanation. Hindus and Buddhists might like that explanation.

You’ve probably heard the expression, “probable cause.” Probable cause usually refers to motive but may involve other factors. If lighting strikes in the same place twice, what are the odds? Three times? Four? If it happens hundreds of times, you’ll probably be assuming there is a cause other than standard weather conditions alone. Maybe there is a body of cloud producing water next to a mountain with a metal rod shooting up where it happens. You won’t assume there is no exceptional cause for the anomaly. Each lightning strike would be in the past, or you wouldn’t have observed it, so you’ll say the odds are 100%, but could you predict the next strike? Yes, because using probabilistic abduction, you would assume there was some cause.

While any stock broker’s attorney would have to inform you that past results are no guarantee of future performance, if you knew the cause underlying the data collected thus far, you would have a better basis for predicting future lightning strikes. You might be like an insider that would have to refrain from investing due to a conflict of interest.

Now what the magician does to defy odds is a trade secret. Is it a miracle? Probably not. This is how causes and probabilities work together. Normally improbable things that happen anyway, deserve explanations. Was it just a fluke? Or was there a cause? What was the most probable cause? The question applies to checking facts. It applies to the prodigies of entertainment. And it applies to life itself. It’s probabilistic abduction.

The problem with probabilistic abduction is that it requires access to a complete inventory of the possibilities, many of which we’ve probably failed to contemplate. When we see a magic show, we only have access to that inventory if we are a fellow magician, and even then, we may be impressed by a magician who knows more than we do. We can’t just assume that we are seeing miracles. We can assume there is a list of tricks shared among magicians in a very private world of people mastering them for fun and profit.

In other settings, we’re caught off guard. Have you been pranked lately? The arts and crafts of magic can easily be added to other areas of innovation. Technology loves magic and magic loves technology. And when you can fool people in one setting, you can fool them in another. Scammers love it. Every time another warranty company calls your mobile phone, you’re already onto it. And if I hadn’t been offered millions of dollars from my friends in Nigeria, I might have believed it was really Eric Schmidt, the CEO of Google, trying to friend me on a jobs board recently, because he wanted to invest in the CounterChecker.

I understand causality and motive. I don’t just believe everything I see with my senses. What are the odds when I consider the alternative explanations? When the face value odds seem too remote to be true, or too coincidental to be coincidences, they probably are. What parent didn’t ever warn their children, “if it seems too good to be true, it probably is”?

I live in Florida. Scammers abound here. I think they prefer warm weather. The anomalies we see in this world, beg for causal explanations. Our scam detecting ability kicks in because of it. And it also kicks in for good stuff, like what game was involved in getting us here to this moment we call now. If it’s not an illusion, the odds are 100% that it happened. But what is the explanation? I’ll explore that down the road in other blogcast episodes. But you’ve probably already guessed. The explanation is poly astronomically maximized awesomeology. Pamalogy, for short.

For now, having looked at causality and probabilistic abduction, I’m going to turn to how this all applies to the truth machine.

Let’s review. In my last blogcast, I mentioned several key factors in determining truth with certainty. I started with pure logic. We gave that the name foundationism. When we talk about probable explanations in terms of odds, like we have been, it’s pure logic. Foundationism is all about deductive logic and inference.

Next, I showed you how foundationism stands in contrast to coherentism. Coherentism is a set of ideas that generally reside in our opinions about the observable world. Coherentism tries to add everything together into a big picture of the world that makes sense – sort of like a completed crossword puzzle. I told you this is what ideologies like conservatism and progressivism do. They are assumptions that fit everything they see nicely together and make sense so long as other points of view are assumed to be wrong.

After that, I told you about evidentialism. Evidentialism was all about data. Whatever the evidence presents, our opinion about what is true, should be based on it. Coherentists may take that evidence and apply it to their worldview, trying to see where it fits into the crossword puzzle they build in their heads. If it doesn’t fit their worldview, they either suffer from something we call “cognitive dissonance,” or they make adjustments to their view.

Coping this way, is easier than you think. The old adage, “there are exceptions to every rule” always acts as a cushion. You seldom overturn a person’s worldview over with a handful of contradictory evidence. Another such cushion is denial. Seeing contradictory evidence, a coherentist can assume the other side is misinformed. And lastly, there are clouds. Illusionists call this closure. Clouds look like things that have meaning to us. We ignore the parts that don’t match the patterns we anticipate.

With all these epistemology terms now on the table, now lets see how we’ll use them in the truth machine.

In the CounterChecker, when a researcher offers a critique of a fact-check or a counter to a fact-check, or a counter to a counter, they grade the article based on all these ways of knowing. It results in a score for each of these categories. The results might say something like, “foundational logic, 100%” Or, more typically, foundational logic 10%, coherentist assumptions, 60%, causal connection, 40%, reliabilist verification 20%, truth tracking 0%.

Any article could be scored from 0-100% in any of these categories. The public could use this as a measure of the extent that a statement was proven to be true. It’s really what we should expect from a truth machine.

And it will do much more. It will force coherentists to hash out their differences to derive the truth through dialog. This is where we bring in another philsopher, Georg Hegel, who believed the best way to teach and to learn was through oppositional dialog. Teachers call this, “dialectics.” It’s why the truth machine is set up with teams of ideologically opposed researchers.

Now you might not expect researchers who sharply disagree with one another to play fairly, especially when politics is involved, but I’ve anticipate this and found a way to cheat-proof the system. If you want to know how, you’ll have to sign a non-disclosure agreement. There’s some remarkable technology an innovation involved here.

What I can tell you is that it will include subjecting both sides to penalties when they break them. Better yet, the opponents will make the calls. Bad calls can be challenged and result in penalties, as well. It’s part of the rules of the machine.

I can also tell you that each article gets scored based on the types of violations against the general rules it makes in fairly determining the truth. The types of violations are counted and the number of each type of violation is also counted, resulting in an objective score for h0w reliable the article is. Failure to provide proof or evidence is a violation of a fact claim. The research is judged by teams of opponents based on the quality of their evidence, their logic, their explanations of causality and the assessment of the reliability of their methodology.

To avoid getting a bad score on an article, all a researcher has to do is follow genuinely objective rules of research. If they don’t, the other side is all but guaranteed to call them on it. Similarly, points are leveled against those who make claims of violations unfairly. This serves as a restrainer against cheating the system with shallow claims or penalties.

Habitual rule breakers won’t last long on teams because their bad scores will lower the team’s reputation. The only way to win is to present arguments with as little bias as possible.

It’s not a perfect machine. Researchers will rarely have access to the data needed to track the truth every time. Conspiracy theories will still exist. Not everyone will believe in the machine, but it will still help us work out our differences. It will help shape better policies. And it can be used to assess the truth in many areas, not just political ones.

OK. Time to summarize. I started this blogcast by looking at the game of life itself. What is its cause? How long is time? We explored something I’d call “probabilist abduction” and I told you that maybe all that we see is a grand illusion. Those are pretty crazy sounding statements until you look at the math and start talking to quantum physicists. I don’t pretend to be either a mathematician or a physicist, but I might tell you, based on probabilistic abduction, that contrary to your experience, it is untrue that your consciousness is subject to time. Instead, time seems to be subject to consciousness.

It’s a cool thought and one I can prove probabilistically, but it deserves further explanation. Next time, I’m going to touch on it some more, so you can start to see what is so awesome about awesomeology. For now, I just want to make sure you are aware of what I mean when I say that context matters when talking about what is true. If you tell me my name is James, as a Pamalogist, I can both agree and disagree. In the context of considering what I am as a perceiving being in some not immediately apparent explanation for consciousness, I would say, maybe I’m not James. Maybe I’m something, or even many things, very different than James. Whereas, in the context of getting by in every day life, apart from that discussion, if you ask me what my name is, I’ll say James Carvin.

Thanks for joining me. Ciao!

URL for sharing this transcript page: https://pamalogy.com/2021/12/21/probability/

URL for sharing this podcast: https://player.captivate.fm/episode/bb595857-8533-4f10-8d4e-934f7145b561

URL for sharing just the audio file: https://podcasts.captivate.fm/media/2118dc43-dd7b-4a02-88c8-92f88cad77b5/episode5-probability.mp3

Previous: Certainty

Up Next: Religion